An Introduction to L. Ron Hubbard

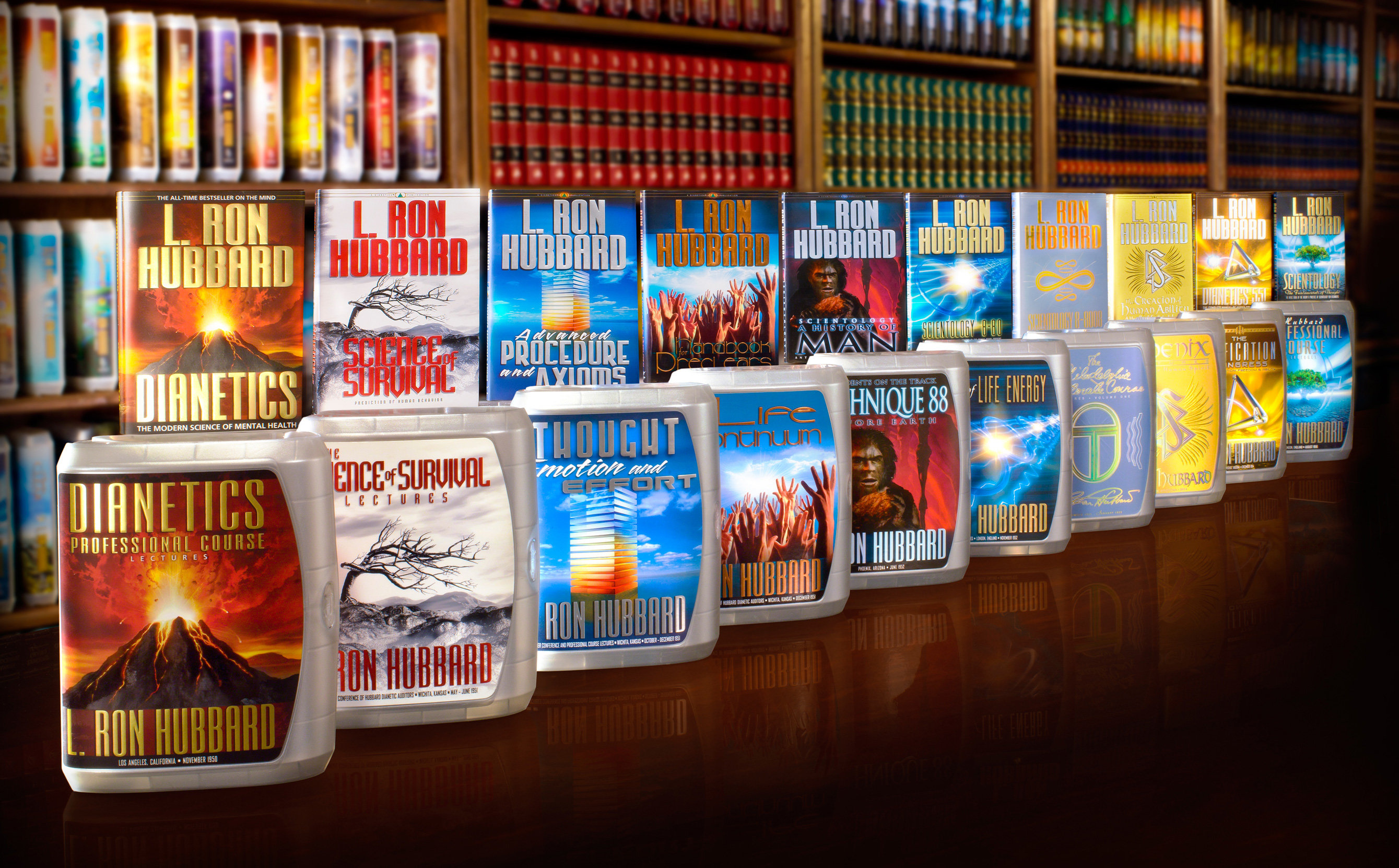

There are only two tests of a life well lived, L. Ron Hubbard once remarked: Did one do as one intended? And were people glad one lived? In testament to the first stands the full body of his life’s work, including the more than ten thousand authored works and three thousand tape-recorded lectures of Dianetics and Scientology. In evidence of the second are the hundreds of millions whose lives have been demonstrably bettered because he lived. They are the generations of students now reading superlatively, owing to L. Ron Hubbard’s educational discoveries; they are the millions more freed from the lure of substance abuse through L. Ron Hubbard’s breakthroughs in drug rehabilitation; still more touched by his common sense moral code; and many millions more again who hold his work as the spiritual cornerstone of their lives.

Although best known for Dianetics and Scientology, L. Ron Hubbard cannot be so simply categorized. If nothing else, his life was too varied, his influence too broad. There are tribesmen in Southern Africa, for example, who know nothing of Dianetics and Scientology, but they know L. Ron Hubbard, the educator. Similarly, there are factory workers across Eastern Europe who know him only for his administrative discoveries; children in Southeast Asia who know him only as the author of their moral code and readers in dozens of languages who know him only for his novels. So, no, L. Ron Hubbard is not an easy man to categorize and certainly does not fit popular misconceptions of “religious founder” as an aloof and contemplative figure. Yet the more one comes to know this man and his achievements, the more one comes to realize he was precisely the sort of person to have brought us Scientology—the only major religion to have been founded in the twentieth century.

What Scientology offers is likewise what one would expect of a man such as L. Ron Hubbard. For not only does it provide an entirely unique approach to our most fundamental questions—Who are we? From where did we come and what is our destiny?—but it further provides an equally unique technology for greater spiritual freedom. So how would we expect to characterize the founder of such a religion? Clearly, he would have to be larger than life, attracted to people, liked by people, dynamic, charismatic and immensely capable in a dozen fields—all exactly L. Ron Hubbard.

“So how would we expect to characterize the founder of such a religion? Clearly, he would have to be larger than life, attracted to people, liked by people, dynamic, charismatic and immensely capable in a dozen fields—all exactly L. Ron Hubbard.”

The fact is, if Mr. Hubbard had stopped after only one of his many accomplishments, he would still be celebrated today. For example, with some fifty million works of fiction in circulation, including such monumental bestsellers as Fear, Final Blackout, Battlefield Earth and the ten-volume Mission Earth series, Mr. Hubbard is unquestionably among the most acclaimed and widely read authors of all time. His novels additionally earned some of the literature’s most prestigious awards and he is very truthfully described as “one of the most prolific and influential writers of the twentieth century.”

His earlier accomplishments are equally impressive. As a barnstorming aviator through the 1930s, he was known as “Flash Hubbard” and broke all local records for sustained glider flight. As a leader of far-flung expeditions, he is credited with conducting the first complete Puerto Rican mineralogical survey under United States protectorship and his navigational annotations still influence the maritime guides for British Columbia. His experimentation with early radio directional finding further became the basis for the LOng RAnge Navigation system (LORAN); while as a lifelong photographer, his work was featured in National Geographic and his exhibits drew tens of thousands.

Among other avenues of research, Mr. Hubbard developed and codified an administrative technology that is utilized by organizations of every description, including multinational corporations, charitable bodies, political parties, schools, youth clubs and every imaginable small business. Likewise Mr. Hubbard’s internationally acclaimed educational methods are utilized by educators from every academic quarter, while his equally acclaimed drug rehabilitation program routinely proves doubly and even triply more effective than any similarly aimed program. Yet however impressive these facts of his life, no measure of the man is replete without some appreciation of what became his life’s work: Dianetics and Scientology. (See the L. Ron Hubbard Series edition, Philosopher & Founder: Rediscovery of the Human Soul.)

The story is immense, wondrous and effectively encompasses the whole of his existence. Yet the broad strokes are these: By way of a first entrance into a spiritual dimension, he tells of a boyhood friendship with indigenous Blackfeet Indians in Helena, Montana. Notable among them was a full-fledged tribal medicine man locally known as Old Tom. In what ultimately constituted a rare bond, the six-year-old Ron was both honored with the status of blood brother and instilled with an appreciation of a profoundly distinguished spiritual heritage.

What may be seen as the next milestone came in 1923 when a twelve-year-old L. Ron Hubbard began an examination of Freudian theory with a Commander Joseph C. Thompson—the only United States naval officer to study with Freud in Vienna. Although neither the young nor later Ron Hubbard was to ever accept psychoanalysis per se, the exposure once again proved pivotal. For if nothing else, as Mr. Hubbard phrased it, Freud at least advanced an idea that “something could be done about the mind.”

“The story is immense, wondrous and effectively encompasses the whole of his existence.”

The third crucial step of this journey lay in Asia, where an L. Ron Hubbard, then still in his teens, spent the better part of two years in travel and study. He became one of the few Americans of the age to gain entrance into fabled Tibetan lamaseries scattered through the Western Hills of China and actually studied with the last in a line of royal magicians descended from the court of Kublai Khan. Yet however enthralling were such adventures, he would finally admit to finding nothing either workable or predictable as regards the human mind. Hence his summary statement on abiding misery in lands where wisdom is great but carefully hidden and only doled out as superstition.

Upon his return to the United States in 1929 and completion of his high-school education, Mr. Hubbard enrolled in George Washington University. There, he studied engineering, mathematics and nuclear physics—all disciplines that would serve him well through later philosophic inquiry. In point of fact, L. Ron Hubbard was the first to rigorously employ Western scientific methods to questions of a spiritual nature. Beyond a basic methodology, however, university offered nothing of what he sought. Indeed, as he later admitted with some vehemence:

“It was very obvious that I was dealing with and living in a culture which knew less about the mind than the lowest primitive tribe I had ever come in contact with. Knowing also that people in the East were not able to reach as deeply and predictably into the riddles of the mind, as I had been led to expect, I knew I would have to do a lot of research.”

That research consumed the next twenty years. Through the course of it, he would move amongst twenty-one races and cultures, including Pacific Northwest Native American settlements, Philippine Tagalogs and aboriginal people of then remote Caribbean isles. In the simplest terms, his focus lay with two fundamental questions. First, and extending from experimentation conducted at George Washington University, he sought out a long-speculated life force at the root of human consciousness. Next and inextricably linked to the first, he searched for a unifying common denominator of life—a universal yardstick, as it were, with which to determine what was invariably true and workable as regards the human condition.

What amounted to a first philosophic plateau came in 1938 with a now legendary manuscript entitled “Excalibur.” In essence it proposed life to be not a random series of chemical reactions, but instead driven by some definable urge underlying all behavior. That urge, he declared, was Survive! and it represented the single most pervasive force among all living things. That Man was surviving was not a new idea. That here was the sole common denominator of existence—this was entirely new and therein lay the signpost for all research to follow.

“That Man was surviving was not a new idea. That here was the sole common denominator of existence—this was entirely new and therein lay the signpost for all research to follow.”

The Second World War proved both an interruption of research and a further impetus: the first owing to service in both the Atlantic and Pacific as a commander of antisubmarine patrols; the second because if anything underscored the need for a workable philosophy to resolve the human condition, it was the unmitigated horror of global conflict. Hence, another summary statement from L. Ron Hubbard at the midpoint of his journey:

“Man has a madness and it’s called war.”

The culmination of research to this juncture came in 1945 at the Oak Knoll Naval Hospital in Oakland, California. Left partially blind from damaged optic nerves and lame with hip and spinal injuries, then Lieutenant L. Ron Hubbard became one of five thousand servicemen under treatment at Oak Knoll for injuries suffered in combat. Also among them were several hundred former prisoners of internment camps, a significant percentage of whom could not assimilate nutrition and were thus effectively starving. Intrigued by such cases, Mr. Hubbard took it upon himself to administer an early form of Dianetics. In all, fifteen patients received Dianetics counseling to relieve a mental inhibition to recovery. What then ensued and what factually saved the lives of those patients was a discovery of immense ramifications. Namely, and notwithstanding generally held scientific theory, one’s state of mind actually took precedence over one’s physical condition. That is, our viewpoints, attitudes and overall emotional balance ultimately determined our physical well-being and not the reverse. Or as L. Ron Hubbard himself so succinctly phrased it: “Function monitored structure.”

Thereafter Mr. Hubbard tested workability on a broad selection of cases drawn from a cross section of American society, circa 1948. Among those case studies were Hollywood performers, industry executives, accident victims from emergency wards and the criminally insane from a Georgia mental institution. In total, he brought Dianetics to bear on more than three hundred individuals before compiling sixteen years of investigation into a manuscript. That work is Dianetics: The Original Thesis. Although not initially offered for publication, it nonetheless saw extensive circulation as hectographed manuscripts circulated within scientific/medical circles. Moreover, such was popular response, Mr. Hubbard soon found himself besieged with requests for further information. In eventual reply, he authored what became the all-time bestselling work on the human mind: Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health.

Without question, here was a cultural landmark. In what would prove a telling prediction, then national columnist Walter Winchell proclaimed:

“There is something new coming up in April called Dianetics. A new science which works with the invariability of physical science in the field of the human mind. From all indications it will prove to be as revolutionary for humanity as the first caveman’s discovery and utilization of fire.”

If Winchell’s statement was bold, it was nonetheless accurate; for with Dianetics came the first definitive explanation of human thinking and behavior. Here, too, was the first means to resolve problems of the human mind, including unreasonable fears, upsets, insecurities and psychosomatic ills of every description.

At the core of such problems lay what Mr. Hubbard termed the reactive mind and defined as that “portion of a person’s mind which is entirely stimulus-response, which is not under his volitional control and which exerts force and the power of command over his awareness, purposes, thoughts, body and actions.” Stored within the reactive mind are engrams, defined as mental recordings of pain and unconsciousness. That the mind still recorded perceptions during moments of partial or full unconsciousness was dimly known. But how the engram impacted physiologically, how it acted upon thinking and behavior—this was entirely new. Nor had anyone fathomed the totality of engramic content as contained in the reactive mind and what it spelled in terms of human misery. In short, here lay a mind, as Mr. Hubbard so powerfully phrased it, “which makes a man suppress his hopes, which holds his apathies, which gives him irresolution when he should act, and kills him before he has begun to live.”

If ever one wished for incontrovertible proof of Dianetics efficacy, one need only consider what it accomplished. The cases are legion, documented and startling in the extreme: an arthritically paralyzed welder returned to full mobility in a few dozen hours, a legally blind professor regaining sight in under a week and a hysterically crippled housewife returned to normalcy in a single three-hour session. Then there was that ultimate goal of Dianetics processing wherein the reactive mind is vanquished entirely, giving way to the state of Clear with attributes well in advance of anything previously predicted.

Needless to say, as word of Dianetics spread, general response was considerable: more than fifty thousand copies sold immediately off the press, while bookstores struggled to keep it on shelves. As evidence of the workability grew—the fact Dianetics actually offered techniques any reasonably intelligent reader could apply—response grew even more dramatic. “Dianetics—Taking U.S. by Storm” and “Fastest Growing Movement in America” read newspaper headlines through the summer of 1950. While by the end of the year, some 750 Dianetics groups had spontaneously mushroomed from coast to coast and six cities boasted research foundations to help facilitate Mr. Hubbard’s advancement of the subject.

That advancement was swift, methodical and at least as revelatory as preceding discoveries. At the heart of what Mr. Hubbard examined through late 1950 and early 1951 lay the most decisive questions of human existence. In an early but telling statement on the matter, he wrote:

“…if many before him had roved upon that track, they left no signposts, no road map and revealed but a fraction of what they saw.”

“The further one investigated, the more one came to understand that here, in this creature Homo sapiens, were entirely too many unknowns.”

The ensuing line of research, embarked upon some twenty years earlier, he described as a track of “knowing how to know.” In a further description of the journey, he metaphorically wrote of venturing down many highways, along many byroads, into many back alleys of uncertainty and through many strata of life. And if many before him had roved upon that track, they left no signposts, no road map and revealed but a fraction of what they saw. Nevertheless, in the early spring of 1952 and through a pivotal lecture in Wichita, Kansas, the result of this search was announced: Scientology.

An applied religious philosophy, Scientology represents a statement of human potential that even if echoed in ancient scripture is utterly unparalleled. Among other essential tenets of the Scientology religion: Man is an immortal spiritual being; his experience extends well beyond a single lifetime and his capabilities are unlimited even if not presently realized. In that respect, Scientology represents the ultimate definition of a religion: not just a system of beliefs, but a means of spiritual transformation.

How Scientology accomplishes that transformation is through the study of L. Ron Hubbard scriptures and the application of principles therein. The central practice of Scientology is auditing. It is delivered by an auditor, from the Latin audire, “to listen.” The auditor does not evaluate nor in any way tell one what to think. In short, auditing is not done to a person and its benefits can only be achieved through active participation. Indeed, auditing rests on the maxim that only by allowing one to find one’s own answer to a problem can that problem be resolved. Precisely to that end, the auditor employs processes—precise sets of questions to help one examine otherwise unknown and unwanted sources of travail.

What all this means subjectively is, of course, somewhat ineffable; for by its very definition auditing involves an ascent to states not described in earlier literature. But in very basic terms it may be said that Scientology does not ask one to strive toward higher ethical conduct, greater awareness, happiness and sanity. Rather, it provides a route to states where all simply is—where one becomes more ethical, able, self-determined and happier because that which makes us otherwise is gone. While from an all-encompassing perspective and the ultimate ends of auditing, Mr. Hubbard invited those new to Scientology with this:

“We are extending to you the precious gift of freedom and immortality—factually, honestly.”

“We are extending to you the precious gift of freedom and immortality—factually, honestly.”

The complete route of spiritual advancement is delineated by the Scientology Bridge. It presents the precise steps of auditing and training one must walk to realize the full scope of Scientology. Because the Bridge is laid out in a gradient fashion, the advancement is orderly and predictable. If the basic concept is an ancient one—a route across a chasm of ignorance to a higher plateau—what the Bridge presents is altogether new: not some arbitrary sequence of steps, but the most workable means for the recovery of what Mr. Hubbard described as our “immortal, imperishable self, forevermore.”

Yet if Scientology represents the route to Man’s highest spiritual aspirations, it also means much to his immediate existence—to his family, career and community. That fact is critical to an understanding of the religion and is actually what Scientology is all about: not a doctrine, but the study and handling of the human spirit in relationship to itself, to other life and the universe in which we live. In that respect, L. Ron Hubbard’s work embraces everything.

“Unless there is a vast alteration in Man’s civilization as it stumbles along today,” he declared in the mid-1960s, “Man will not be here very long.” For signs of that decline, he cited political upheaval, moral putrefaction, violence, racism, illiteracy and drugs. It was in response to these problems, then, that L. Ron Hubbard devoted the better part of his final years. Indeed, by the early 1970s his life may be charted directly in terms of his search for solutions to the cultural crises of this modern age.

“Unless there is a vast alteration in Man’s civilization as it stumbles along today, Man will not be here very long.”

That he was ultimately successful is borne out in the truly phenomenal growth of Scientology. There are now more than ten thousand groups and organizations in well over 150 nations using the various technologies of Dianetics and Scientology. That his discoveries relating to the human mind and spirit form the basis of all else he accomplished is, in fact, the whole point of this introduction. Thus, what is presented in pages to follow—in the name of better education, crime-free cities, drug-free campuses, stable and ethical organizations and cultural revitalization through the arts—all this and more was derived from discoveries of Dianetics and Scientology. Yet given the sheer scope of accomplishment—as an author, educator, humanitarian, administrator and artist—no such treatment can be entirely complete. For how can one possibly convey, in a few dozen pages, the impact of a life that so deeply touched so many other lives? Nonetheless, this succinct profile of the man and his achievements is provided in the spirit of what he himself declared:

“If things were a little better known and understood, we would all lead happier lives.”